Revolution

BY bRETT NEveu

Dramaturgy by Tanya Palmer & Peter Ruiz

wITCHES

“The term Weird Sisters was first used by Scots writers as a sobriquet for the Fates of Greek and Roman mythology. Through its appearance in Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles, the expression passed to William Shakespeare.”

Fate, Greek Moira, plural Moirai, Latin Parca, plural Parcae, in Greek and Roman mythology, any of three goddesses who determined human destinies, and in particular the span of a person’s life and his allotment of misery and suffering. Homer speaks of Fate (moira) in the singular as an impersonal power and sometimes makes its functions interchangeable with those of the Olympian gods. From the time of the poet Hesiod (8th century BC) on, however, the Fates were personified as three very old women who spin the threads of human destiny. Their names were Clotho (Spinner), Lachesis (Allotter), and Atropos (Inflexible). Clotho spun the “thread” of human fate, Lachesis dispensed it, and Atropos cut the thread (thus determining the individual’s moment of death). The Romans identified the Parcae, originally personifications of childbirth, with the three Greek Fates. The Roman goddesses were named Nona, Decuma, and Morta.

Clotho

The Fates in ancient Greek were called the Moirai. This translates as “allotted portion” or “share.” The idea was that the Fates would deal out humankind’s allotted portions of life. The three Fates each had a different role in the process of handing out fate or “portions.”

First of all, there was Clotho, the “Spinner.” When a human was in the womb, Clotho had the duty of weaving the threads of their life. Greek myth often uses textile metaphors to convey intangible destiny. The metaphor often appears in descriptions as well as in art, as the weaving of threads on a loom, or in some cases spinning fibers into yarn.

Each thread represented one soul’s life. This thread would follow the path of a human’s life, including their future choices and actions, and the consequences that could be created. Clotho would begin spinning the thread while the human was in the womb, and so she is often referred to during pregnancies or during the birth of human beings.

“He must look to meet whatever events his own fate and the stern Klothes (Clotho) twisted into his thread of destiny when he entered the world and his mother bore him.”

(Homer, Odyssey 7.193)

The choices of mankind were not absolute. Instead, there was freedom in choice, and the fate of a human depended on conditional choices. The Fates would take all decisions and outcomes into account when they wove the thread.

Lachesis

Lachesis was the second of the Moirai, or Fates, and her role was to measure the thread of a human’s life. Her name translates as “the Allotter” which fits her role as the one who allots a portion of mortal life to each soul. Lachesis would determine how long a human would live, and hence how many trials they would face in their life. Within the thread lay the fate of each soul.

“This is the word of Lachesis, the maiden daughter of Ananke (Necessity), souls that live for a day, now is the beginning of another cycle of mortal generation where birth is the beacon of death.”

(Plato, Republic 617c)

Atropos

The third sister was Atropos, whose name translates as “the un-turnable or she who cannot be turned.” Her name refers to her unshakeable position as the most stubborn of the Fates. Atropos was the one to cut the thread of fate, and at the point of the cut, the mortal life would end. Thus, Atropos resembles the death of a human. After the cut, a soul would then be sent to the Underworld for judgment, after which, it would be sent to Elysium, the Fields of Punishment, or the Fields of Asphodel.

“Comes the blind Fury with th’abhorred shears, / And slits the thin spun life.”

(John Milton, Lycida, 1. 75)

Atropos’ role was vital, she chose how each person would die. She decided on the circumstances of their death — whether that was nobly or ignobly, was up to her. The Fates were often depicted as old women and sometimes as young goddesses, so it majorly depends on artistic preference. Many representations show Atropos as an old woman — as she chose when people would die — and Clotho as a young woman — as she was often present when women gave birth.

Their appearance may not have been absolute, but one consistency in their depiction is with the loom or yarn. The thread is always a staple feature to identify the Fates. They are often creating tapestries depicting the life of a human.

Morai Lineage

In Plato’s Republic, the Moirai are suggested to be the daughter of Ananke. Ananke was the primordial deity of inevitability or necessity. She passed on an element of this role to her children, the Fates, as they came to symbolize both the necessity of birth, life, and death, but also the inevitability of fate, and the events destined to occur in a human’s life.

Alternatively, the Fates are suggested to be the daughters of Nyx, the goddess of night. In Hesiod’s Theogony, he writes: “Also Night [Nyx] bare the destinies, and ruthless avenging Fates, who give men at their birth both evil and good to have, and they pursue the transgressions of men and gods… until they punish the sinner with a sore penalty.” (Lines 221–225)

This is a slightly darker interpretation, as the Fates as the daughters of Night suggest a gloomy and pessimistic outlook on the cycle of the soul in Greek myth. However, as the daughters of Ananke, the Fates are not negative or positive, they are objective, in the sense that “these things will just happen.”

A third suggestion is that the Fates are the daughters of Themis, the goddess of justice and divine order. Hence, the Fates are continuations of the divine order of life — without them, the cycle of souls would be in chaos. This points to an idea that the Greeks had about the importance of natural order, or balance. Life and death were in opposition to the destructive nature of chaos.

Fate, Portion, and Share

The Fates, or Moirai, and their literal translation as the “allotters,” is closely associated with the ancient Greek word: meros, meaning “part” or “lot” and moros “fate” or “doom.” These terms are commonly used alongside the Fates, as they were seen to give “lots” and assign “doom” or “fate,” often with somber connotations of death. However, these terms in ancient Greek are also used in common, daily activities, such as giving a meros or “portion” of food to each participating diner.

Ancient Greek thought was often concerned with the shares allotted to humankind, and how each person would receive their portion; whether this be in such commonalities as food, land, or treasure, or abstracts such as glory or death. To take someone’s share or lot, you would be taking their rightful portion as assigned by fate.

“While the Weird Sisters certainly reflect Christian beliefs about witches in Shakespeare’s day, they also come across as more ancient beings rooted in paganism. The three witches call to mind the three Fates, or Moirai, in ancient Greek and Roman mythology. These goddesses determined how long each mortal would live—one spinning the thread of life, another measuring it, and the third cutting it. Norse mythology had similar beings called Norns who also controlled life: Urd, Verdandi, and Sculd. Interestingly, Urd, the goddess of the past, shares her etymology with the Old English word wyrd (pronounced with two syllables, sounding a little like wayward), which later became weird. In Shakespeare’s time, weird meant fate; it was centuries later that the word took on today’s meaning of being strange. Perhaps Shakespeare saw the Weird Sisters as divine beings who merely showed Macbeth who he really was, rather than witches who seduced him into damnation.”online can make all the difference.

The Norns were the Norse goddesses of fate, represented as three sisters named Urd, Verdandi, and Skuld. They lived underneath the world tree, where they wove the tapestry of fate. In Scandinavian mythology, each life was believed to be a single string in this tapestry and the length of that string correlated to the length of each life. Everything was thought to have been preordained and even the gods had threads in the tapestry, although the Norns did not allow the gods to see their own strings.

The meaning of their names:

Urd is similar to the past tense of the verb verđa, "to become" and thus means something like "Became" or "Happened." It is cognate with Old English wyrd, "fate, destiny" ansd related words in Old High German and Old Saxon. Verdandi is the present participle of verđa, "Becoming" or "Happening." Skuld is derived from the modal verb skulu, which is cognate with English "shall" and "should," and probably then means "Is-to-be" or "Will-happen."[6]

In this way, the Norns signify "the past, the present, and the future."[7] Given both their number and their role(s), it is perhaps unsurprising that they have often been compared to the Greek Fates (Moirae).

The role of the Norns exemplifies the ultimately fatalistic nature of the Norse mythic/religious complex,[9] where the future was seen as being ultimately preordained, as evidenced by Odin's sacrifice of an eye for a vision of the end times (Ragnarök) and Balder's precognitive dreams of his own demise. Indeed, every being, both divine and human, had an alloted place in this cosmic order, which was foretold by these three Wyrd (Urd) sisters.

Hecate was the chief goddess presiding over magic and spells. She witnessed the abduction of Demeter’s daughter Persephone to the underworld and, torch in hand, assisted in the search for her. Thus, pillars called Hecataea stood at crossroads and doorways, perhaps to keep away evil spirits. Hecate was represented as single-formed, clad in a long robe, holding burning torches; in later representations she was triple-formed, with three bodies standing back-to-back, probably so that she could look in all directions at once from the crossroads. She was accompanied by packs of barking dogs.

sOULMATE

A soulmate is a person with whom one has a feeling of deep or natural affinity. This may involve similarity, love, romance, platonic relationships, comfort, intimacy, sexuality, sexual activity, spirituality, compatibility and trust.

SOULMATE SYMBOLS

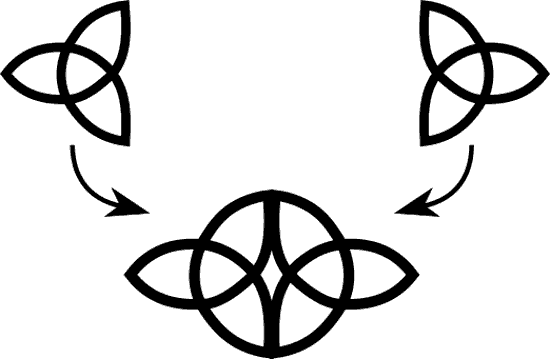

Serch Bythol

The Serch Bythol is an ancient Celtic symbol whose roots lie deep in mystery. Literally translated from Welsh as “everlasting love,” this relatively obscure knot is made by placing two Celtic Triquetra knots together. The Triquetra represents the sacred three of mind, body, and spirit within one human. When two Triquetras are placed together, it symbolizes the addition of a second person to the sacred three.

tHE pIKORUA

The Pikorua, or double-twist, is a powerful Māori symbol. The shape itself resembles the twisted fronds of the Pikopiko fern, a plant native to New Zealand. With two separate strands twisting together and joining as they rise, the Pikorua represents different people coming together to meet on common ground. It is an important sign of peace and understanding, with Māori people often giving Pikoruas to friends, family, and spouses as presents.

The separate strands represent the individuals, while the singular structure represents the relationship between the two and their sacred union. Whether platonic or romantic in nature, the relationship is a soulmate bond that cannot be broken. The two beings stay together throughout all the twists and turns of life, navigating through the world with a singular intention and purpose.

Further Reading on Soulmates

FRIENDSHIP RITUALS

FLOWER FRIENDS

With regard to the exchange of names, a slightly different custom prevails among the Bengali coolies. Two youths, or two girls, will exchange two flowers (of the same kind) with each other, in token of perpetual alliance. After that, one speaks of the other as "my flower," but never alludes to the other by name again--only by some roundabout phrase.

BALONDA BEER CEREMONY

The Balonda are an African tribe inhabiting Londa land, among the Southern tributaries of the Congo River. They were visited by Livingstone, and the following account of their customs is derived from him:--

"The Balonda have a most remarkable custom of cementing friendship. When two men agree to be special friends they go through a singular ceremony. The men sit opposite each other holding hands, and by the side of each is a vessel of beer. Slight cuts are then made on the clasped hands, on the pit of the stomach, on the right cheek, and on the forehead. The point of a grass-blade is pressed against each of these cuts, so as to take up a little of the blood, and each man washes the grass-blade in his own beer vessel. The vessels are then exchanged and the contents drunk, so that each imbibes the blood of the other. The two are thenceforth considered as blood-relations, and are bound to assist each other in every possible manner. While the beer is being drunk, the friends of each of the men beat on the ground with clubs, and bawl out certain sentences as ratification of the treaty. It is thought correct for all the friends of each party to the contract to drink a little of the beer. The ceremony is called 'Kasendi.' After it has been completed, gifts are exchanged, and both parties always give their most precious possessions." Natural History of Man. Rev. J. G. Wood. Vol: Africa, p. 419.

BLOOD PACT CEREMONY OF RWANDA

In traditional Rwanda, the blood pact was often used to seal the friendship between individuals and families. The ceremony needed four groups of people: the officiating person, the two friends and the witnessing people. The facilitator will call for the people’s attention and introduce the ceremony by telling people the reason of the meeting. The two friends who are going to seal their friendship with a blood pact will bring a knife, sorghum flour, a leaf of erythrina abyssinica (Fabacées), and a mat. The facilitator will take a knife and cut the wound of the two friends who are going to seal their friendship with the blood pact. Then he will get the blood and mix it with the sorghum flour on the erythrina abyssinica leaf, and the facilitator will give it to the two friends to drink. He will say the following words: “I unite you, if anyone of you breaks the pact with his friend or with the close or extended family members or with his friends, he will die.” He will add that there will be a curse on the one who breaks the pact.

The two friends get up at the same time, hug each other, and exchange gifts. The gift may be a cow, a goat, or a sheep. They could also give a hoe as a gift.

The purpose of this blood pact was to prevent people from wrong doing and to avoid losing time in judging or solving the conflicts among people. According to Beattie, “the participation in it involved a ceremonial exchange of blood, and implied reciprocal obligations of mutual aid and hospitality, a breach of which involved danger and perhaps death for the guilty party.”

FRIENDSHIP BRACELETS

Friendship bracelets are ancient,but their resurgence is modern. The modern popularity of friendship bracelets started in the 1980s when they were seen during protests about the disappearances of Mayan Indians and peasants in Guatemala. The friendship bracelets were brought into the United States by religious groups for use in political rallies.

Friendship bracelets can have many meanings and symbolic uses, such as friendship, folk art, or social statements Although it is generally accepted that the origins of these colorful bands lie with the indigenous people of Central and South America, some decorative knots can be traced back to China from 481 to 221 BC.

Friendship bracelets first became popular in the United States during the 1970s. As they are unisex, they are commonly worn by both male and female teenagers and children. They are now popular throughout the world. Friendship bracelets can be worn on various occasions; for example, they are ideal as a fashion accessory at the beach because they are made of materials that will not be easily destroyed and with which one can swim freely.

According to tradition, one ties a bracelet onto the wrist of a friend as a symbol of friendship and may wish for something at that moment. The bracelet should be worn until it is totally worn out and falls off by itself to honour the hard work and love put into making it. The moment at which the band falls off on its own, the wish is supposed to come true.

“During Kartik, many Benarsi Hindu women perform a collective daily puja, a form of ritual worship, in which they raise Krishna from infancy to adulthood, culminating in his marriage to the plant‐goddess Tulsi toward the end of the month. During this puja, women assume the devotional stance of the gopis. Just as the gopis are believed to have gathered around Krishna in a circle in the original circle dance, so Kartik puja participants gather in a circle around icons of Krishna and other deities; and just as the gopis of long ago adored Krishna with song and dance, puja participants worship him with song and devotional oerings. Popular Krishna traditions equate the gopis with the faithful female servants, known collectively as the sakhis, who accompany and serve the divine couple Radha‐Krishna. Sakhi means “female friend,” and in Kartik puja circles, women are enjoined to refer to themselves and to each other only with this term. 2 In the course of discussing the meaning of the term sakhi with Kartik puja participants, I found that participants tended to dene it rst in terms of human friendship, bringing up the term's connection to Krishna mythology only at my prompting. When I probed further, I was told also of a ritual of becoming (banana) or tying (bandhana) sakhi, in which women exchange vows of lifelong friendship. Once I learned of the existence of this ritual, I began to ask informants about it explicitly. About twenty of the thirty‐six women I formally interviewed in the course of my research conrmed its existence and described for me both the act of ritually becoming sakhi and the bond that is thereby established, including the meaning of the relationship and the obligations that it entails. Almost all of these women claimed the authority of experience, contending that they themselves had established ritually sealed sakhi relationships that they value and strive to maintain.

Six informants explicitly described the sakhi bond among women as one that imitates or replicates divine models.

All six invoked the relationship between Radha and her sakhis, or the relationships that Radha's sakhis shared with one another, as the root (mul) or role model (adarsh) for the sakhi bond. One woman, for example, proclaimed, “My relationship with my sakhi is like the relationship of Radha and her sakhis. And we hope that we will be together in the same way for our whole lives.” Another invoked as a model the relationship shared by Radha and Krishna as well, noting, “The way Krishna used to love Radha and the kind of deep aection that the sakhis have for each other, similarly we also become sakhi.”

This seeming collapse of an erotic, male‐female relationship—that between Radha and Krishna—with the relationships of deep friendship attributed to Radha and her female friends adumbrates a larger issue surrounding sakhi relationships as they were described to me: the sakhi bond in many ways imitates or echoes some of the social and emotional aspects of the marital bond. Like marriage, the sakhi relationship is considered unique, deeply intimate, and entailing specic rules and obligations. I would argue that the sakhi bond that informants in Benares described to me deploys religious and marital imagery in ways that sacralize ongoing relationships among female friends, according them social and even religious legitimacy and establishing a socially valid place for them in women's lives. Although these relationships exist only at the margins of patriarchal social discourse, which denes women largely in terms of male‐centered kinship relationships, they are reported to be of great importance to many of the women who enter into them.

All but one of the women who spoke with me about the sakhi bond armed the existence of a ritual whereby the bond is sealed. The essential elements of this ritual practice include an exchange of gifts and food, the swearing of an oath, and the presence of a deity, who acts as a witness. This is how one informant, Gita, described the process of becoming sakhi:

You buy bangles, bindi, hair ribbons, clothes, and some ornaments—like earrings—to give. By giving these, this is tying sakhi. If the girls are unmarried, then they give each other these gifts and go to the Sakshi Vinayak temple and say, “Considering you as a witness, we will remain sakhi.” And they take an oath that “we will remain friends with each other, participate in each other's auspicious and inauspicious functions, in birth and death, marriage, and so forth. And at the time of death, I will be with you.”

The gifts exchanged most often include those like the ones Gita described: clothes, makeup, jewelry, bindis (the decorative dots that Indian women place on their foreheads), and sindur, a bright red or orange powder.that married women place in the part of their hair. Two informants described the items exchanged as “stuff for marital auspiciousness” (suhag ka saman). Other women stressed the exchange of food, especially sweets and pan, as crucial to the sealing of the bond. Sakhis not only feed one another, but they also self -consciously exchange with one another food polluted by their saliva. One elderly informant described the process as follows:

In the ritual of becoming sakhi, there are some puja things—sweets, yogurt, pan—and the sakhis feed each other these things. … For example, if you and I were becoming sakhi, then I would feed you sweets, you would feed me sweets, and then you would bite o some pan and I would chew it; and I would bite o some pan, and you would chew it. And they say to each other, “Everyone may leave us, whether it is husband, or mother, or father, or brother, but we will never leave eachother!”

The Different types of love

1. Philia — Affectionate Love

Philia is love without romantic attraction and occurs between friends or family members. It occurs when both people share the same values and respect each other — it’s commonly referred to as “brotherly love.”

Love Catalyst: The mind

Your mind articulates which friends are on the same wavelength as you and who you can trust.

How to Show Philia:

Engage in deep conversation with a friend.

Be open and trustworthy.

Be supportive in hard times.

2. Pragma — Enduring Love

Pragma is a unique bonded love that matures over many years. It’s an everlasting love between a couple that chooses to put equal effort into their relationship. Commitment and dedication are required to reach “Pragma.” Instead of “falling in love,” you are “standing in love” with the partner you want by your side indefinitely.

Love Catalyst: Etheric (Subconscious)

The subconscious drives partners towards each other. This feeling comes unknowingly and feels purposeful.

How to Show Pragma:

Continue to strengthen the bond of long-term relationships.

Seek and show effort with your partner.

Choose to work with your partner forever.

3. Storge — Familiar Love

Storge is a naturally occurring love rooted in parents and children, as well as best friends. It’s an infinite love built upon acceptance and deep emotional connection. This love comes easily and immediately in parent and child relationships.

Love Catalyst: Causal (Memories)

Your memories encourage long-lasting bonds with another individual. As you create more memories, the value of your relationship increases.

How to Show Storge:

Sacrifice your time, self or personal pleasures.

Quickly forgive harmful actions.

Share memorable and impactful moments.

4. Eros — Romantic Love

Eros is a primal love that comes as a natural instinct for most people. It’s a passionate love displayed through physical affection. These romantic behaviors include, but are not limited to, kissing, hugging and holding hands. This love is a desire for another person’s physical body.

Love Catalyst: Physical body (Hormones)

Your hormones awaken a fire in your body and must be satiated with romantic actions from an admired partner.

How to Show Eros:

Admiring someone’s physical body.

Physical touch, such as hugging and kissing.

Romantic affection.

5. Ludus — Playful Love

Ludus is a child-like and flirtatious love commonly found in the beginning stages of a relationship (a.k.a. the honeymoon stage). This type of love consists of teasing, playful motives and laughter between two people. Although common in young couples, older couples who strive for this love find a more rewarding relationship.

How to Show Ludus:

Flirt and engage in whimsical conversation.

Spend time together to laugh and have fun.

Exemplify childlike behavior together.

6. Mania — Obsessive Love

Mania is an obsessive love towards a partner. It leads to unwanted jealousy or possessiveness — known as codependency. Most cases of obsessive love are found in couples with an imbalance of love towards each other. An imbalance of Eros and Ludus is the main cause of Mania. With healthy levels of playful and romantic love, the harm of obsessive love can be avoided.

Survival instinct drives a person to desperately need their partner in order to find a sense of self-value.

How to Avoid Mania:

Recognize obsessive or possessive behavior before acting upon it.

Focus on yourself more versus another person.

Put trust into your relationships.

7. Philautia — Self Love

Philautia is a healthy form of love where you recognize your self-worth and don’t ignore your personal needs. Self-love begins with acknowledging your responsibility for your well-being. It’s challenging to exemplify the outbound types of love because you can’t offer what you don’t have.

Love Catalyst: Soul

Your soul allows you to reflect on your necessary needs and physical, emotional and mental health.

How to Show Philautia:

Create an environment that nurtures your well-being.

Take care of yourself like a parent would care for a child.

Spend time around people who support you.

8. Agape — Selfless Love

Agape is the highest level of love to offer. It’s given without any expectations of receiving anything in return. Offering Agape is a decision to spread love in any circumstances — including destructive situations. Agape is not a physical act, it’s a feeling, but acts of self-love can elicit Agape since self-monitoring leads to results.

Love Catalyst: Spirit

Your spirit creates purpose bigger than yourself. It motivates you to pass kindness on to others.

How to Show Agape:

Dedicate your life to improving the lives of others.

Stay conscious of your actions for the good of humankind.

Offer your time and charity to someone in need.

aCADMEIC RESOURCES TO CONSIDER

Interpersonal rituals in marriage and adult FRIENDSHIP

This is an academic resource- Particularly of interest are Escape Episodes, Celebration Rituals, and Play Rituals which I have bolded!

“The first major category of friendship rituals, Social/Fellowship Rituals, accounted for 64.9 percent (309) of all reported friendship rituals and was divided into four categories: Enjoyable Activities, Getting-Together Rituals, Established Events, and Escape Episodes. Each of these subtypes defines a different aspect of friends' ritualistic social and fellowship activities. The most frequent subtype in the Social/Fellowship Ritual category was Enjoyable Activities, which accounted for 31.5 percent (150) of all friendship rituals and 48.5 percent of its major category. The items in this subcategory are joint social or recreational activities or pastimes that have in common pleasurable, desirable, and/or leisure qualities.

Getting-Together Rituals were the second most frequent friendship subtype. They accounted for 23.1 percent (110) of all reported friendship rituals and 35.6 percent of the general category. Getting-Together rituals involve times/ways/means for friends physically to get together and keep in touch, excluding telephone calls.

The third most frequently reported Social/Fellowship ritual subtype was the Established Event. Accounting for 6.7 percent (32) of all friendship rituals (10.4% of the Social/Fellowship Rituals), these rituals have much in common with both the ritual types of Enjoyable Activities and Getting-Together, but have as their distinguishing quality a tendency to be special, highly planned, prized, and/or reserved events or activities, such as annual trips, outings, and vacations with friends; moreover, most have an established place in the history of the friendship.

Escape Episodes comprised 3.6 percent (17) of all friendship rituals identified and accounted for 5.5 percent of the superordinate category. Escape Episodes are specifically designed for being away with friends from others, the routines of life, or external pressures.

The second major category of rituals is the Idiosyncratic/Symbolic Ritualtype, which includes 3 subcategories, accounted for 9.5 percent (45) of all reported friendship rituals. The ritual subtypes in this superordinate category were: Celebration Rituals, Play Rituals, and Favorites.

Celebration Rituals were the most frequent subtype (49 percent of the generalcategory) and represented 4.6 percent (22) of all friendship rituals. Similar to the marriage subtype Celebration Rituals, these rituals are particular means or routines for holidays, birthdays, anniversaries, or other special events.

Representing 3.4 percent (16) of all reported friendship rituals and 35.5 percent of the Idiosyncratic/Symbolic Ritual category were Play Rituals. These rituals take many forms, such as joking, kidding, teasing, playing pranks on one another, or being generally silly. Also included are all the ways friends share humor and laughter, including silly phrases and "inside jokes."

The most infrequently reported ritual subtype category was the ritual subcategory Favorites, which accounted for only 1.5 percent (7) of all friendship rituals and approximately 16 percent of its major category. Identical to the marriage ritual type Favorites, this type includes the shared, often symbolic, places friends go, things they regularly eat, purchase, or give, and activities that are often idiosyncratic, always most preferred, among friends.

The third most frequently reported major ritual type, accounting for 9 percent (43) of all friendship rituals, was the Communication Ritual. These are rituals for simply keeping in touch with friends via cards and/or telephone calls. Regular phone calls were common among friends, as illustrated by a monthly calling ritual one woman reported she and her friend have maintained "for 21 years and over 5 continents."

Accounting for 8.4 percent (40) of all reported friendship rituals, the category Share/Support/Vent includes rituals developed specifically for social, emotional, or spiritual sharing and support between friends. This type of ritual also represents the necessary release of frustrations between friends about issues related to, for example, family, marriage, work, and social pressures.

Tasks/Favors, accounting for 6.9 percent (33) of the friendship rituals, involve doing something with and/or for a friend.

The most infrequently reported ritual category was Patterns/Habits/Mannerisms and comprised a mere 1.3 percent (6) of all friendship rituals. This ritual type is parallel with the marriage type Patterns/Habits/Mannerisms and similarly relates the interactional, territorial, and/or siruational patterns and habits friends develop.”

Risk rituals and the female life-course: negotiating uncertainty in the Transitions to WomaNHOOD AND MOTHERHOOD

This is another academic resource on Risk Rituals with a focus on womanhood and motherhood.

“Moore and Burgess (2011) introduced the concept of ‘risk rituals’ to describe behavioural adaptations to an anticipated risk that become routine practices. Risk rituals are distinct from ad hoc adaptations to a perceived risk, as well as idiosyncratic responses. By contrast, risk rituals have cultural reference-points and reflect socially-circumscribed problems of uncertainty and vulnerability. Examples discussed by Moore and Burgess (2011) include self-checking for cancer, recycling, face-mask wearing, use of hand sanitiser – where, to be clear, these practices become habitual and entrenched.”

“Similarly, for most of the young female first-year undergraduates who took part in our 2008 study, the need to make friends, to ‘be social’, and to consume large volumes of alcohol created great ambivalence. To deal with these problems, the young female participants undertook precautionary measures to negotiate social situations characterised by perceived vulnerability, uncertainty, and distrust. The core themes that emerged from the interview and focus group data reflect this: they were staying in and with the group one came out with, looking out for and after other group members, and being watchful.”

“The first of these themes was usually expressed in terms of there being ‘safety in numbers’. ‘You go out together and come back together’, was how one young woman put it. Others commented on the importance of group size, often preferring small groups, or, as one female Fresher put it, ‘not so big groups, because you know where everyone is then’. In contrast, a number of interviewees believed that the typical female victim was a lone woman who had been separated from her friendship group: this was a potent symbol in young women’s accounts of risky socialising, central also to young women’s accounts in Bailey et al’s (2015) study. Some, for example, talked about seeing young women collapsed on pavements outside nightclubs, and, interestingly, the common feature to all these stories was the fact of these women being on their own and separated from their friends.”

“Take, by way of example, the function of the young women’s ‘getting ready’ ritual. Half of the female interviewees (13) described a lengthy period (two or three hours) of ‘getting ready’ that generally preceded going out in public to socialise. This ‘getting ready’ session involved mainly or solely female members of the social group meeting at a group member’s home, getting dressed, applying make-up, listening to music, and drinking (mainly wine) together. This was a key step in many of the young women’s narratives of ‘going out for a big night out’, and, again, it was shaped by a sense of risk. Several of the interviewees explicitly framed this ritual as a means of planning precau tionary behaviour for the night ahead, such as discussing whether they had taxi numbers,when they should leave a pub or club, who they would meet up with later in the evening, codes they would use if one of their number wanted to leave a club/bar with a man.Similarly, in a study of UK female undergraduates’ experiences of pre-drinking and club drinking, Bancroft (2012) notes the role of the ‘getting ready’ ritual in minimising risk by, amongst other things, allowing group members to agree meeting points once inNa club, to mitigate the dual risks of becoming isolated from the group and becoming subject to unwanted sexual attention. He tellingly describes the getting-ready phase of ‘big nights out’ as ‘highly directed, bounded, and ritualised.”

In other words, they served a solidaristic function. The ‘drinking circle’, ‘getting ready’ ritual, and collaborative mapping of surroundings are not just about managing uncertainty: they are pro-social activities through which young women forge relationships and affirm a sense of belonging.